“The novel is consistently amusing, particularly when Hamburger offers barbed observations about the banalities of tourist culture.”

— The New York Times

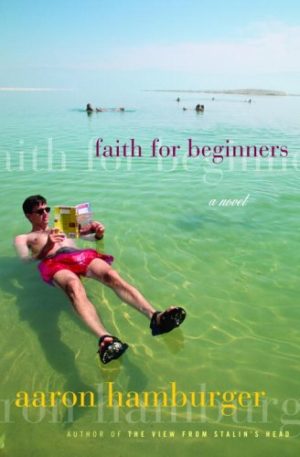

An acclaimed short-story writer has created a miraculous first novel about an American family on the verge of a breakdown–and an epiphany.

In the summer of 2000, Israel teeters between total war and total peace. Similarly on edge, Helen Michaelson, a respectable suburban housewife from Michigan, has brought her ailing husband and rebellious college-age son, Jeremy, to Jerusalem. She hopes the journey will inspire Jeremy to reconnect with his faith and find meaning in his life… or at least get rid of his nose ring.

It’s not that Helen is concerned about Jeremy’s sexual orientation (after all, her other son is gay as well). It’s merely the matter of the overdose (“Just like Liza!” Jeremy had told her), the green hair, and what looks like a safety pin stuck through his face. After therapy, unconditional love, and tough love… why not try Israel?

Yet in seductive and dangerous surroundings, with the rumbling of violence and change in the air, in a part of the world where “there are no modern times,” mother and son become new, old, and surprising versions of themselves.

Funny, erotic, searingly insightful, and profoundly moving, Faith for Beginners is a stunning debut novel from a vibrant new voice in fiction.

For two weeks, their troika of air-conditioned buses shuttled them up and down the Holy Land, up from the snows of Mount Hermon (no snow in summer) down to the sandy wastes of the Negev (hot, poisonous winds and dreary scenery).

Mrs. Michaelson applauded for an orchestra of Russian immigrants playing Gershwin at a kibbutz in the Galilee, though she didn’t really like Gershwin. Too showy.

She ate pita pounded thin and then toasted over an open fire by Bedouins in a desert camp in the Negev. “Good?” they asked. “Good, good!” she reassured them.

She watched Mr. Michaelson, who’d mysteriously dropped the title of “Doctor” when he got sick, rape the Holy Land of its souvenirs: heart-shaped blue glass eyes, inflatable camels, Dead Sea mud masks, a book of Golda Meir’s favorite falafel recipes, an antique Roman coin that came with a certificate of authenticity.

She received a welcome kit with a miniature cake and an airline-sized bottle of kosher red wine (she confiscated Jeremy’s bottle while he was in the shower), a Michigan Miracle Daily Bulletin Xeroxed on goldenrod paper, and a plastic bottle of FROM SAND TO LAND sand, which Jeremy dumped into her glass of wine one night at dinner to prove he wasn’t the least bit tempted to steal a sip.

She pressed flesh with the mayors of Tel Aviv, Rishon LeTzion, and Eilat, where they stayed in a nice hotel with free samples of peppermint foot lotion, which she used to massage her bunions.

She witnessed a phalanx of ten women dressed all in black standing by the side of the highway near Megiddo Junction. Perfectly silent and still, the Women in Black carried signs in Hebrew, English, and Arabic calling for the end of the “Occupation.”

She quickly learned the two ways to say, “No thanks, I’m stuffed,” in Hebrew, a matter of life or death in a country where tourists were apt to be pelted with unwanted extra helpings. The first expression meant, “I’ve had enough to eat.” The other, which wasn’t particularly nice, was, “I’m so full I’m going to explode like an Arab.”

She posed for a picture beside a camel tied to a parking meter and invited Jeremy, standing a few feet away from everyone as usual with one of his cigarettes, to pose too. And just for the picture, could he take out the safety pin he’d seen fit to stick through his nose? (There was nothing they could do about the green stripes in his hair, though by pretending to pat him on the head, she often managed to smooth out the sharp edges of his “faux Mohawk,” a pyramid of hair cemented with gel.)

It wasn’t a safety pin.

“It looks like a safety-pin,” Mrs. Michaelson said. “What’s the difference?”

Jeremy pulled at the metal, stretching out his nostril. “This is sterilized. Also, for your information, camels aren’t the least bit Biblical. They weren’t domesticated until six hundred years after Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.”

At times like this one she saw some of her own awkwardness in him, and she couldn’t help laughing. “Why do I open my mouth?” he said. “You never listen to me, anyway.”

So Mrs. Michaelson stood alone by the un-Biblical camel, blinked away the beads of perspiration dripping into her eyes, and said she enjoyed it. She recalled the dignity of the Women in Black silently protesting near Megiddo, and imagined that by taking the picture, she too was staging a silent protest. As soon as the camera flashed, several charming Bedouin boys jumped down from the olive trees and came running at them, shouting, “Money! Money!”

She clipped a photo of Barak from the Herald Tribune because he looked exactly like her father when he’d been Ehud Barak’s age. Back then, her father woke up at six a.m. to work at his grocery stand, then came home late, his hands chafed raw from washing vegetables in ice water. She loved him, but she used to hate touching his hands.

Mostly she sweated. Miserably. They all sweated. Everywhere the Michiganders traveled, guides and drivers and souvenir hawkers told them how unlucky they were to visit Israel during a Sharav (Hebrew) or a Hamsin (Arabic), a blistering heat wave. These Hamsins, (most Israelis preferred the Arabic name), scalded the Levant every summer, but there hadn’t been one this bad in a while.

“I think maybe fifty years, giving or taking,” said Baruch, their Israeli driver, as they churned up Highway 1 from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. She preferred Baruch to Igor, who stank of dill. Beside her snored Mr. Michaelson, leaking threads of drool from the corners of his mouth. She was so glad to see him enjoy a good sleep, she didn’t care how he looked. Jeremy sat four rows behind them and pushed up his hair. He’d caused a sensation that morning by pinning his nametag to the zipper of his camouflage cut-offs.

“The last time we had such a Hamsin, it was a few weeks after our War for Independence,” said Baruch, his shirt unbuttoned down to his navel. He was always trying to impress her by careening around the edges of sheer cliffs or aiming their bus at fruit stands in picturesque stone alleys. “I was a boy, but I still remember everywhere there was shooting and crazy men with guns in their hands.”

“Terrifying,” she said as if she cared, but she’d heard so many Hamsin-stories by then, they blended together. She was surprised there was no commemorative T-shirt.

“That’s only the start, my dear Shoshana.” Baruch always called her “Shoshana,” the Hebrew word for rose, though it wasn’t her name. “In a Hamsin, a man can get all turned around. Normal becomes crazy and crazy becomes normal.”

Mrs. Michaelson had dreamed of exactly that kind of transformation for her son when she’d signed them up to visit Israel. No luck so far, and now they had only five days left before they returned home. She felt ashamed when she thought of how naively she’d pushed them all to come, and at such expense.

Their bus grunted uphill, slouching beneath a heraldic banner across Highway 1: Peugeot welcomed them to Jerusalem, Mrs. Michaelson’s final, though perhaps best, hope. If Jeremy was going to find himself, where could be more fitting than the capital of the Jews’ home turf?

Reviews

“In his debut novel, FAITH FOR BEGINNERS, Aaron Hamburger offers a hilarious spin on the ancient travel-as-self-discovery formula in the shape of a family trip to Israel. Along the way, Hamburger directs his sharp satirical eye at a wide range of targets, and any Jew who has embarked on a package tour of the “original Old Country” will laugh out loud at the details. And, without ever compromising his gift for comedy, he also manages to introduce profound questions at every stage – about the morality of the Israeli occupation, about the demands (and attractions) of conformity and about the difficulty of finding faith in a nonsensical world.”

— Newsday

“As the Michaelsons endure “Millenium Marathon 2000,” a prepackaged trip through the Holy Land in air-conditioned buses, the sadder, grimmer sides of Israel slowly overwhelm both them and Jeremy’s new lover. The novel is consistently amusing, particularly when Hamburger offers barbed observations about the banalities of tourist culture.”

— The New York Times

“Precise, finely observed.”

— Philadelphia Inquirer

“A knockout of a novel… The author’s shrewd and satirical look at Judaism, and American and Israeli style, is in the great tradition of Philip Roth, and makes for an absorbing read.”

— Frontiers Magazine (chosen as one of the top five books of 2005)

“A woman hopes a family trip to Israel will help her reclaim her confused, rebellious son in Hamburger’s entertaining, irreverent first novel (after the collection The View from Stalin’s Head). Jeremy’s been at NYU for five years, but he’s still just a junior, and Helen Michaelson, 58, thinks he might have a much-needed spiritual awakening on the “Michigan Miracle 2000″ tour. But while Jeremy’s more interested in cruising Jerusalem’s gay parks, Helen herself is primed for revelation, as she finds that her connection to Judaism and her family is more complicated than she’d thought. Hamburger has an exacting eye for mundane detail and suburban conventions, and in Jeremy he’s created the classic green-haired, pierced college student ranting about social injustice. But beneath Jeremy’s sarcastic, moralizing banter, there’s a convincing critique of Americans’ way of being in the world. In Israel in 2000, the Michaelsons are like Pixar creations trapped in a movie filmed in Super 8—the Middle East may be fraught with political tension, but their biggest problem is the heat outside their air-conditioned bus. Hamburger goes further than witty satire, though, and when the plot takes a dark turn he demonstrates that he’s capable of taking on global issues, even if his characters aren’t.”

— Publishers Weekly

“With humor and insight, Hamburger explores the cultural tension between the nation of Israel and American Jews through the story of the Michaelsons. Helen, the daughter of Russian immigrants, is married to a psychologist suffering from a slow-burning cancer. They have two gay sons. The youngest, Jeremy, is an NYU student and recent suicide-attempt survivor. Helen decides a trip to Jerusalem is what her family needs. With high hopes, she signs them up for the Michigan Miracle 2000. However, they soon feel as if they are in a tourist trap. Helen and Jeremy are driven by a connection to faith to escape the prepackaged experience, albeit in bizarre ways. Helen has an affair with the hirsute rabbi leading the tour group, and Jeremy falls in love with a deaf Palestinian named George. Hamburger engages the reader with wonderfully flawed characters and through the history, legend, and propaganda of modern Jewish life. This novel is highly recommended for anyone who is drawn to stories of family affected by the global political context of everyday life.”

— Booklist

“Aaron Hamburger takes a deceptively simple situation—an American family visiting Israel—and spins a rich, complex, often profound comedy about religion, sex, politics, and love. He has an excellent eye and ear for the absurd, but more important, genuine sympathy for the hopes and confusions all people share under our cartoon surfaces. And nobody has written a better mother and son.”

— Christopher Bram, author of The Lives of Circus Animals

“Aaron Hamburger elucidates a truth about the search for faith: that the journey forward is seldom blissful. In FAITH FOR BEGINNERS, Hamburger peoples a volatile political setting with a handful of characters pursuing transcendence—through culture, through mortality, through the spirit, through the flesh. For Hamburger’s seekers, what transpires is risky, chaotic and surprisingly tender. For his readers, exhilarating.”

— Dave King, author of The Ha-Ha